While patrolling the Manila-Singapore shipping lanes on 22 February 1944, at 07.20, Lt. Cdr. Frank G. Selby sighted masts and smoke some fifteen miles from his submarine, the USS Puffer. An eastbound convoy moving at seven knots.

Not wanting to engage the ships in shallow water, he steamed at high speed on the surface to the north of Subi Besar, from where he would swing south to intercept them in deeper water, free of shoals and navigational hazards. He hoped to catch them at the exit of the Koti passage, where he calculated he had thirty to thirty-seven fathoms (up to about 66m) of water to work with.

At 15.45, with three hours of daylight remaining, Selby picked up two ships, a two-stack camouflaged transport ship and what appeared to be a small destroyer in escort, zigzagging at six-minute intervals. This was not the convoy he had been tracking that morning, but a much bigger ship isolated from its own main convoy, moving west. He decided to ignore his morning targets and go for the big game.

Selby’s plan was to fire four torpedoes set to run at a depth of four meters at the transport, and two set at a depth of two meters at the escort. However, the maneuvers of the ships were such that it took him until 17.04 to bring his stern tubes to bear. Four torpedoes raced away, and he swung his craft sharply to port to bring his bow tubes into firing position. At 17.06.16 and 17.06.28, respectively, he heard two explosions, one was observed about midway between the transport ship’s bow and the forward funnel, the other was unseen but believed to be near the stern, both portside.

Selby’s plan was to fire four torpedoes set to run at a depth of four meters at the transport, and two set at a depth of two meters at the escort. However, the maneuvers of the ships were such that it took him until 17.04 to bring his stern tubes to bear. Four torpedoes raced away, and he swung his craft sharply to port to bring his bow tubes into firing position. At 17.06.16 and 17.06.28, respectively, he heard two explosions, one was observed about midway between the transport ship’s bow and the forward funnel, the other was unseen but believed to be near the stern, both portside.

Through his periscope, Selby observed the ship now almost dead in the water, listing ten degrees to port and veering gently, its steering gone. The USS Puffer closed in and began taking pictures as the escort, undamaged, fled, without making any attempt to set depth-charges. Selby watched as lifeboats were lowered and netting was thrown over the side, as those on board abandoned ship. Men in white (either fatigues or underwear) were seen in the boats. As the scene unfolded, it became clear that the ship would not sink from the damage so far sustained. In fact, some believed that a propeller had again begun to turn. At 17.24, the Puffer delivered the mortal blows, firing her #1 and #2 torpedo tubes at the ship and striking a quarter-length in from the bow and stern respectively. The transport now began to roll to port and settle quickly by her stern.

Selby estimated the transport ship’s length to be 520 to 530 feet (it was in fact 172 meters/570ft) with a weight of at least ten thousand tons, he suspected she was one of the American or European ships captured early in the war by the Japanese. Too late to get close enough to make out the name on the bow, he observed nine or ten characters, but with no sign of the Japanese word 'MARU' to be seen. At 17.35, the transport slipped below the surface, its location given as 03º10’N, 109º15’E, where it would remain unseen by human eyes for the next fifty-eight years.

Selby estimated the transport ship’s length to be 520 to 530 feet (it was in fact 172 meters/570ft) with a weight of at least ten thousand tons, he suspected she was one of the American or European ships captured early in the war by the Japanese. Too late to get close enough to make out the name on the bow, he observed nine or ten characters, but with no sign of the Japanese word 'MARU' to be seen. At 17.35, the transport slipped below the surface, its location given as 03º10’N, 109º15’E, where it would remain unseen by human eyes for the next fifty-eight years.

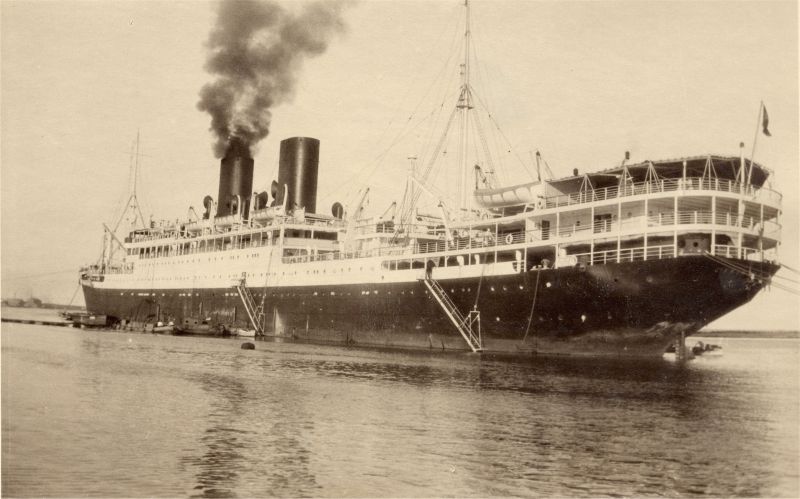

After the war, the Puffer was credited with sinking the Japanese troop transport Teiko Maru, a 20,323-ton displacement ship, which Selby had rightly guessed had started life as the French liner Le D’Artagnan. Built in 1924, she was a member of the huge Messageries Maritimes Fleet, calling at ports from Europe, through South Africa and Madagascar, to Indochina, Australia and New Zealand. The advent of World War II saw the fleet split between the Allies and Vichy France, the D’Artagnan went to Vichy forces until she was captured by the Japanese in 1942. Her life ended on that February day en route from Manila to Singapore, when she encountered the Gato Class Submarine USS Puffer off of North West Borneo. She took down with her 199 Japanese soldiers who were believed to have been bound for shore leave.

The ship’s rediscovery is credited to Vidar Skoglie of the MV Empress, who for over a decade has cruised Malay and Indonesian waters in search of wrecks and is credited with hundreds of discoveries. He found D’Artagnan on 7 July 2002, and visited her on technical charters about once a year. The distance of some 560km from home base in Singapore, and the 72-meter/240ft depth to seabed, kept the numbers of visitors down. Vidar and the Empress are no longer operating technical charters and visits to this far out of the way location might now have stopped entirely.

The Tech Asia connection goes back to April 2006. As part of Underwater Exploration Productions (UEP), with whom we were then involved, we participated in a trip which filmed and updated on the condition of the wreck. Divers were all from the Asia-pacific region and of course, we chartered Empress, as Vidar's ability to successfully run these kinds of trip had no equal at the time, possibly ever since.

The diving was open circuit and whilst a lot of the gear we needed was on the boat or available in Singapore, still a great deal, high capacity steel doubles and extra DPV's included, had to be seafreighted from Manila. The project checklist of spare parts was enormous, given that if we broke something out on site then we may as well have been on the Moon as anywhere else with regard to getting things fixed. But all that was needed arrived and one of our team, Nicolas LeClerc, was kind enough to turn his apartment into the nicest pre-trip workshop we have ever seen. Everybody played their part and by midnight on April 1st an excited group of divers was clearing customs and heading out in to the South China Sea.

The diving was open circuit and whilst a lot of the gear we needed was on the boat or available in Singapore, still a great deal, high capacity steel doubles and extra DPV's included, had to be seafreighted from Manila. The project checklist of spare parts was enormous, given that if we broke something out on site then we may as well have been on the Moon as anywhere else with regard to getting things fixed. But all that was needed arrived and one of our team, Nicolas LeClerc, was kind enough to turn his apartment into the nicest pre-trip workshop we have ever seen. Everybody played their part and by midnight on April 1st an excited group of divers was clearing customs and heading out in to the South China Sea.

The first day saw a couple of shakedown dives on a freighter known as Target Wreck, and then an overnight steam took us to the large (2,700-ton) Japanese destroyer Shimotsuki. Fascinating dive though she makes, another overnight run direct to D’Artagnan was voted on. Arriving mid-morning on the 4th, with anchor down and a descent line secured, we had our first opportunity to look over the wreck. Historic photos show a majestic ship, but the ravages of war and more than half a century of submersion have altered her immeasurably.

The ship lies between fifty-five to seventy-two meters (180-240ft.), listing about sixty-five degrees to port, shrouded in netting, and just below a thermocline that dropped visibility on the first days to about fifteen feet/five meters. Much of the superstructure, formerly the lounges and first- and second-class accommodations, had collapsed into a confused mass of twisted metal. Given the ship’s great size and initially limited visibility, first-dive impressions were those of viewing isolated pieces of a large jigsaw puzzle. I am sure many experienced the feeling of jumping in on a new wreck filled with anticipation and grandiose plans for the engine room, only to surface confused with “Hmm…I think that might have been the bow…?” But after taking a step back and adjusting expectations and letting the knowledge of the ship grow over a couple of dives, a natural momentum starts to build and bring excitement about the next dive. Each dive teams emerged with clearer stories and a greater affinity for the wreck. The pieces of the puzzle started coming together.

Prior to this project, two gentlemen very kindly volunteered us invaluable information. Craig MacDonald, whose father served on the USS Puffer, fleshed out the historical background to the attack using extracts from his manuscript titled at the time "Be Lucky – The History of the Submarine USS Puffer", which contained photographs originally sourced from the estate of Lt. Cdr. Frank Golay. Philippe Ramona sent us some superb images and deck plans, which were of enormous help in planning and navigating the wreck. Both men had a keen interest in the current condition of the ship, and our dives were executed with the purpose of bringing them up-to-date very much in mind.

Prior to this project, two gentlemen very kindly volunteered us invaluable information. Craig MacDonald, whose father served on the USS Puffer, fleshed out the historical background to the attack using extracts from his manuscript titled at the time "Be Lucky – The History of the Submarine USS Puffer", which contained photographs originally sourced from the estate of Lt. Cdr. Frank Golay. Philippe Ramona sent us some superb images and deck plans, which were of enormous help in planning and navigating the wreck. Both men had a keen interest in the current condition of the ship, and our dives were executed with the purpose of bringing them up-to-date very much in mind.

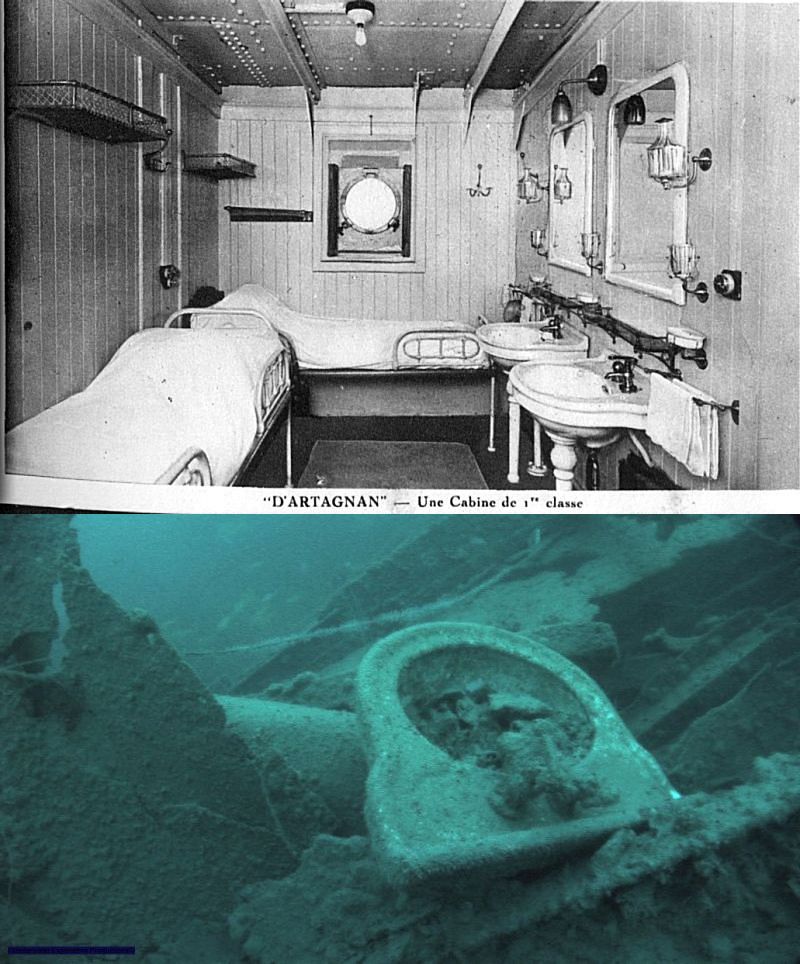

The general deterioration of the upper decks was pronounced, but artifacts like brass cabin fixtures and bathroom fittings are still identifiable amongst the collapsing plating, we were able to correlate these with Philippe’s photographs of the interior of the ship in her life as a liner. The Japanese obviously made no effort to refit her for troop transport, and everything appeared very much in its original form. Ornate French crockery still lies alongside Japanese rifle munitions.

The starboard side of the ship’s hull shows areas devoid of any hull plating, presumably blown off by internal pressures caused by the sinking. These areas provide relatively easy interior access. From the point of tie-in, near the remains of the bridge, to the stern was almost a five-minute scooter ride. Little wonder that previous swim divers had never reported the presence of the props. The one visible propellor, at 71 meters/235ft, is in such a position that if were it turning, it would strike the rudder. This confirms Cdr. Selby’s observation of the stricken ship losing steering control. Quite possibly his second torpedo, presumed to have struck the stern, was what effectively crippled the ship.

Persistence with finding entry points eventually paid off on the last day. Bulkhead collapse, deep silt and bird’s-nests of wiring had put a stop to many attempted penetrations beforehand. Finally though, after navigating passageways as deep as 245 feet (75 meters), two men put a line into the boiler rooms from an access point toward the stern. The ship’s bow was within easier reach and the starboard anchor still in place, but the ship’s name was no longer discernible. Vidar had no recollection of anyone reporting the port anchor, so three divers went on a hunt, and found it laying isolated on the sea bed, draped with a decaying trawl net.

As the days passed and visibility improved, new individual discoveries gave rise to a strong impression amongst divers that this was an absolutely classic wreck, by no means easy, but infinitely rewarding. Rather than transit home and making dives along the way, a unanimous call was made to stay put on D’Artagnan until the last possible diving moment, with nothing more than a short stop for a dive on the Campanilla just out of Singapore. Weighing anchor and heading west, it was unspoken but obvious that everyone’s reflections were on how they could next escape their offices and return to this tremendous site. So many wrecks, so little time …

As the days passed and visibility improved, new individual discoveries gave rise to a strong impression amongst divers that this was an absolutely classic wreck, by no means easy, but infinitely rewarding. Rather than transit home and making dives along the way, a unanimous call was made to stay put on D’Artagnan until the last possible diving moment, with nothing more than a short stop for a dive on the Campanilla just out of Singapore. Weighing anchor and heading west, it was unspoken but obvious that everyone’s reflections were on how they could next escape their offices and return to this tremendous site. So many wrecks, so little time …

References :

Philippe Ramona: http://www.messageries-maritimes.org/d'artag.htm

The USS Puffer in World War II: A History of the Submarine and Its Wartime Crew by Craig R. McDonald

Photographs courtesy of:

Underwater Exploration Productions

USN Historical Center

Philippe Ramona